How to define feminist art in Asia? Historically, such a designation has defied a single framework. Political contexts, aesthetic movements, and the emergence of women’s rights and gender theory have varied too widely across Asian regions. But among the presentations at Art Basel Hong Kong’s Insights sector – devoted to curated booths offering in-depth perspectives on one or two artists represented by Asia-based galleries – there emerges a constellation of women artists whose visionary practices have shaped and challenged the aesthetics of their respective countries. As women have gained greater visibility across Asian societies, these artists, too, have put forth new lenses through which to imagine female futures.

In the canon of Postwar Japanese art, Hideko Fukushima (1927–1997) is a pivotal if under-acknowledged figure. In 1951, she cofounded Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop) one of the most avant-garde collectives in Japan at the time, whose 14 members focused on interdisciplinary collaboration and incorporated new technology into traditional Japanese arts and crafts. She was later introduced to the Art Informel artists in France after critic and artist Michel Tapié saw her work in Japan in 1957. Working in painting, sound, poetry, and stage design, Fukushima sought to transcend medium. Throughout her career she focused on the color blue and the circular form, which she often stamped on canvases or works on paper; this technique, called kataoshi, ran counter the assertive gestures of male Abstract Expressionist artists working at the same time. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, her visual language had shifted to include color-field works. Tokyo-based gallery Standing Pine will show an array of her blue works from this period, like Whither Blue (VII) (1982), a one-meter-by-one meter work in which shades of a Klein-like cobalt blue wash over the canvas in diagonal swaths.

A similarly meditative intensity appears in the work of the late Korean artist Chungji Lee (1941–2021), whose abstract monochromes on canvas are musings on time, labor, and repetition. Lee was one of the few women in the post-Dansaekhwa (monochrome) movement in Korea during the Postwar era. Here, Seoul-based Sun Gallery presents a selection of her works from the 1980s and 1990s, all made by layering paint on canvas with rollers and knives, then scraping at the pigments to create textural stripes and grids on the thick, often earth-toned ground. In the 1990s, Lee introduced calligraphic elements into the strata of underpainting, subtly etching in sayings like ‘Where there is will, there is nothing unachievable’, with a palette knife. Operating within a movement led by men (such as Lee Ufan) and steeped in the rhetoric of restraint, Lee’s work claims repetition not as labor, per se, but rather as persistence – resistance, even.

The work of Han Jin (b. 1979), presented by Seoul-based The Page Gallery, brings gestural abstraction into the present. In her ongoing field research around the Korean peninsula, Han uses sound – echoing footsteps, rustling wind – to sense and grasp the precise moment of standing in indeterminate spaces, often geographical or political borders. In this presentation, she translates these sonic impressions into an installation including a large abstract painting, a video, and drawings, all produced over the past decade. This emphasis on listening reframes abstraction through perceptions grounded in presence rather than assertion.

Sensory attentiveness also threads through the dreamy photography of Rinko Kawauchi (b. 1972), presented by Kyoto-based MtK Contemporary Art. Over the past two decades, Kawauchi has captured disarmingly intimate images of everyday life – children playing, a baby’s tiny hand being held in the hand of an elderly relative – as well as tender encounters with the natural world. Works on view include those from an early-2000s series titled ‘M/E’, which focuses on ephemeral moments from nature (‘M/E’ stands for both ‘Mother Earth’ and ‘I’). Her patient attention to quotidian detail could be seen as a female gaze: With its sustained focus on care, interdependence, and life’s fragility, her photography elevates subjects historically dismissed as minor or sentimental.

At Seoul-based G Gallery, two Korean artists appear in a presentation that spans generations but shares both a traditionally feminine medium and a sense of feminist ethics. Both work in textiles, expanding and exploring fabric’s sculptural potentials. A first-generation Korean installation artist, Yang Juhae (b. 1955) has often worked with inherited fabrics (like her mother’s old bedsheets) to which she applies multiple layers of acrylic before ‘dotting’ their surfaces in a coded language she developed while studying in France. Woo Hannah (b. 1988), who is 33 years younger, shows wearable objects that appear as hybrid body forms. Woo creates colorful pieces reminiscent of animal or human organs with fabrics and scraps sourced from local businesses or workshops. Both artists transform and transmute materials and concepts: Yang makes remnants into sites of endurance and care; Woo proposes an embodiment based on fluid identity and collaboration.

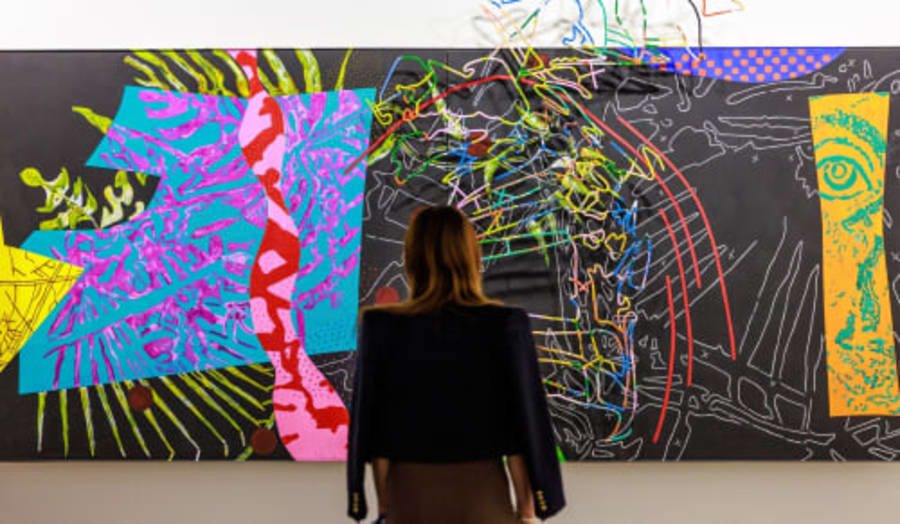

Finally, the New York-based gallery Sapar Contemporary brings together two artists whose work explores powerful women warriors across ancient regional spiritual traditions, including the shamanic beliefs of Kazakh and Mongol nomads, Tibetan Buddhism, and Islam, tearing them out of their temporal constraints. Kazakhstan-born, US-based Aya Shalkar (b. 1996) mixes archaeology with speculative fiction, visualizing civilizations of female warriors and mythical beings (like a self-portrait as centaur) with artifacts and photography. Mongolian artist Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (b. 1979), meanwhile, is a contemporary master of Mongol zurag

(flat, colorful renderings of scenes from everyday life), which she blends with Buddhist iconography, surrealism, and futuristic references to depict contemporary female fighters. For both artists, past, present, and future come together in powerful pictures of feminine badassery, a far remove from theoretical feminism in the Western sense.

Taken together, all these practices resist a singular, unified Asian feminism. Instead, they reveal the breadth of approaches through which women artists across Asia have, for so long, asserted agency – and written their own art histories.

Art Basel Hong Kong takes place from March 27 to 29, 2026. Get your tickets here.

Kimberly Bradley is a writer, editor, and educator based in Berlin. She is a commissioning editor at Art Basel Stories.

Caption for header image: Aya Shalkar in Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Sapar Contemporary.

Published on February 20, 2026.